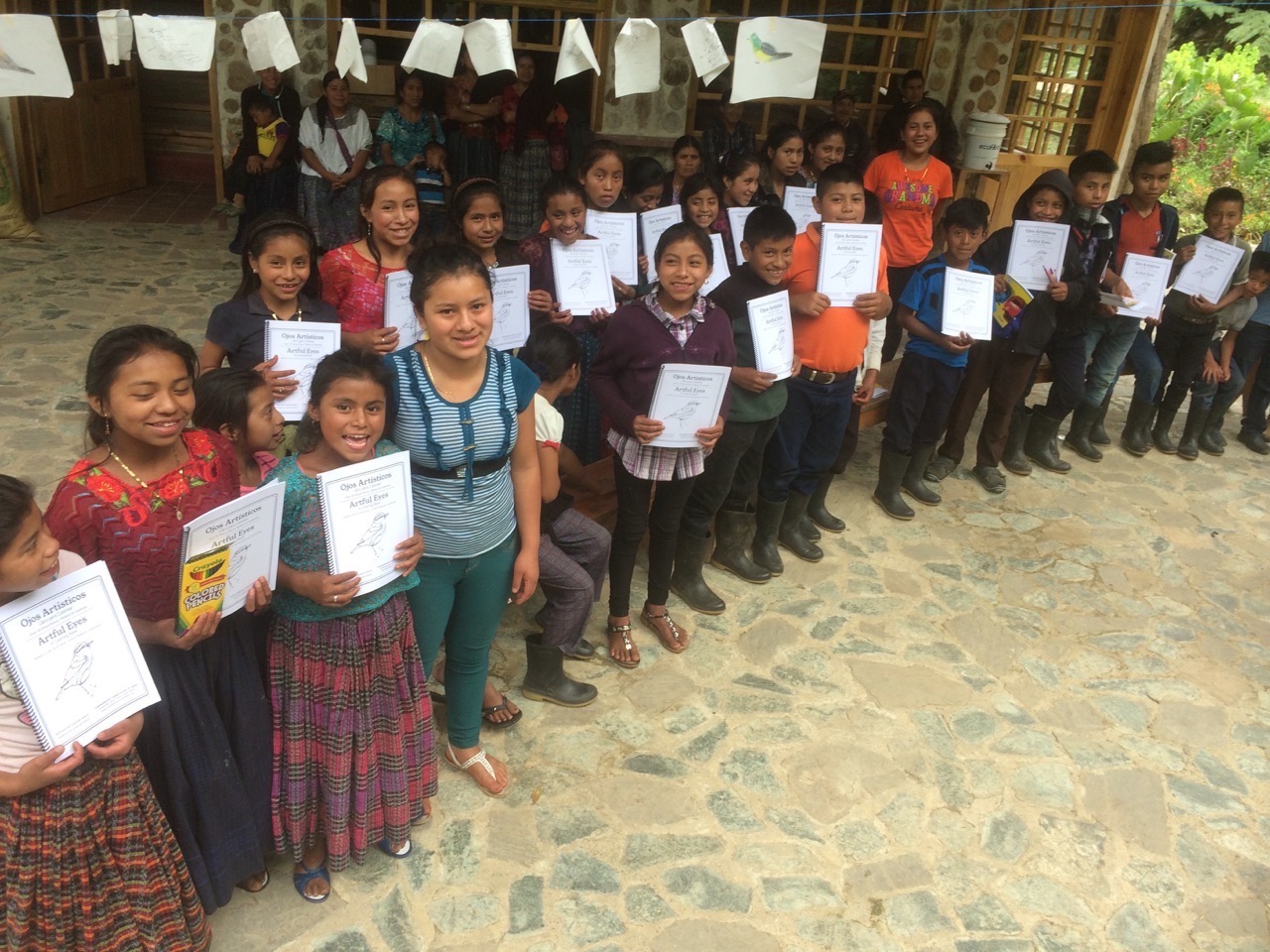

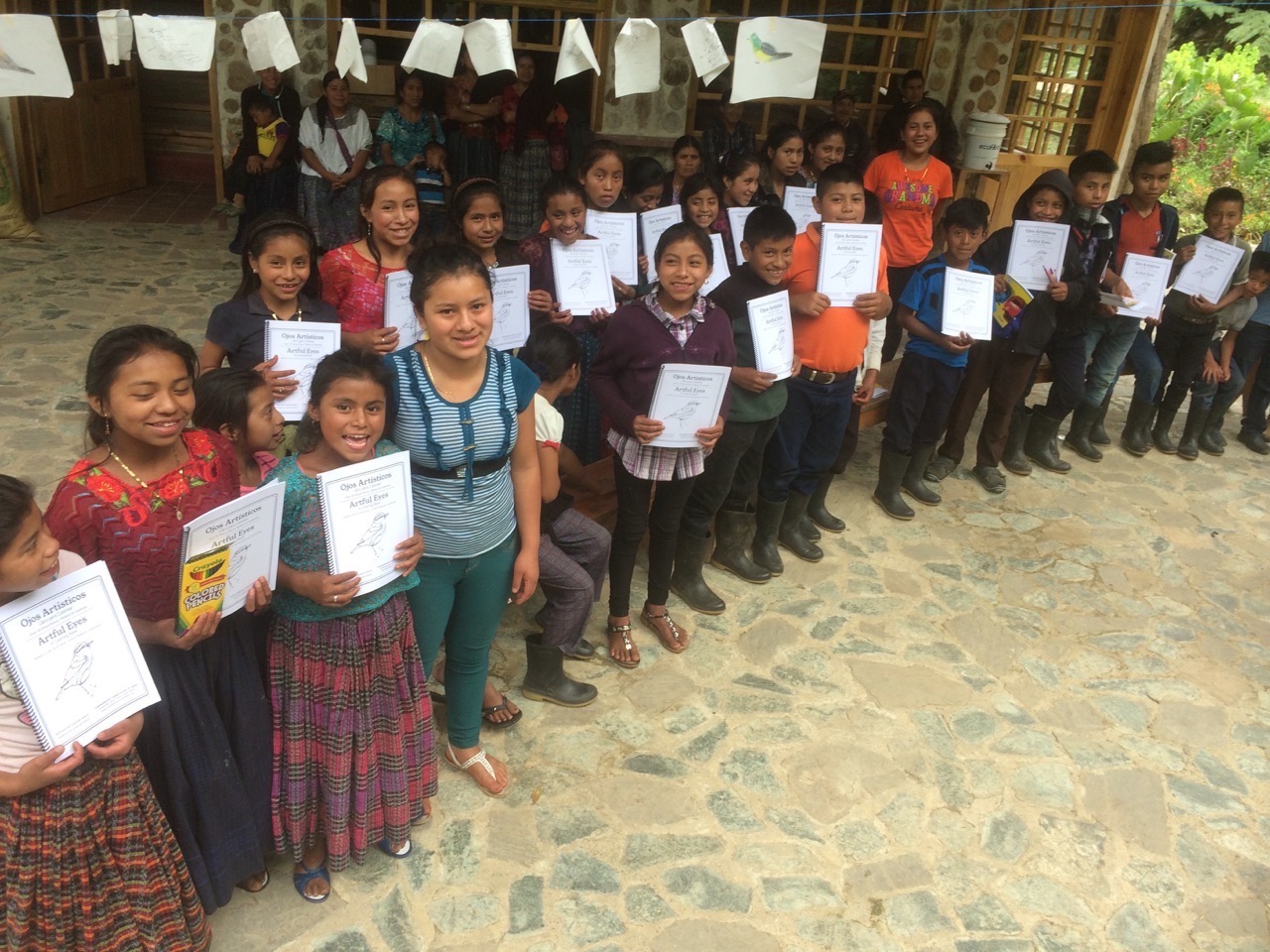

The San Lucas Sequila primary and the two primary schools of Sequila all got a warbler coloring book last week. This year, 2018, CCFC will give 1,200 warbler coloring books to the students that visit CCFC for Kids & Birds.

The San Lucas Sequila primary and the two primary schools of Sequila all got a warbler coloring book last week. This year, 2018, CCFC will give 1,200 warbler coloring books to the students that visit CCFC for Kids & Birds.

CCFC’s Kids & Birds program has a wonderful new resource, the Warbler Coloring Book. Thanks to the excellent art work of CCFC intern and University of Mary Washington Biology major, Savannah Aldrich, CCFC has published a coloring book which includes all the warblers of the region.

Kids & Birds Team for 2018 with Rudy Botzoc. Each member of the entire Kids & Birds team is an alumnae of CCFC’s WALC program. And all of them (with the exception of Josefina) are currently enrolled in either high school or university. Josefina is taking a gap year between high school and university and is the only team member to cover the work on Fridays.

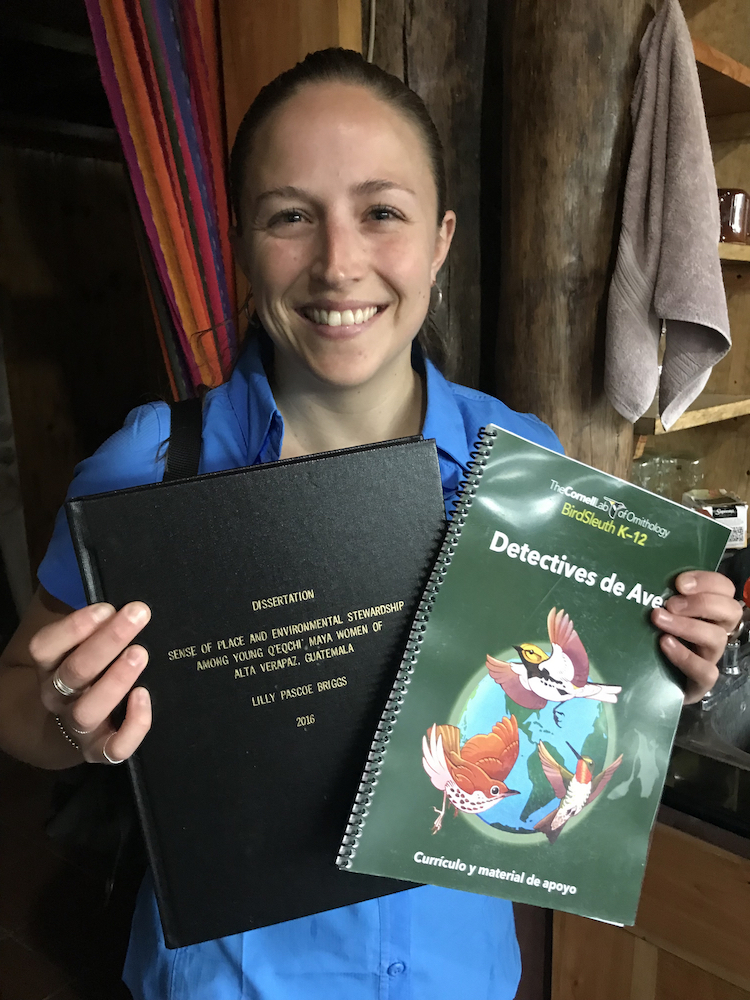

CCFC’s relationship with Lilly Briggs goes back to 2011 when CCFC first began to use Cornell Lab’s BirdSleuth curriculum for it’s Kids & Birds Program. Later Lilly came to CCFC to do her field research for her Ph.D. at Cornell University. Lilly’s research focus was CCFC’s WALC program.

On a recent visit to CCFC, Lilly presented her finished version of her Ph.D. dissertation to the CCFC library along with the most recent version of the BirdSleuth curriculum.

Thanks Lilly! Your research provides important feedback and affirmation for the efforts of WALC.

As we look toward 2018, we are especially excited about the Kids & Birds program. Schools will start arriving the last week of January. Our goal for 2018 is to have 1,200 sixth graders from January to September of 2018.

We need your help. Please contribute to Kids & Birds 2018 and help us reach our goal of having 1,200 students.

Click here to contribute to Kids & Birds

Photo © Dr. Dawn Bowen

Photo © Dr. Dawn Bowen

Photo © Dr. Dawn Bowen

Photo © Dr. Dawn Bowen

One hundred twenty five young women from 43 remote mountain villages arrived at CCFC for the 25 day workshop.

Teachers and staff from Defensores de la Naturaleza came to CCFC for a four teach Kids & Birds teachers training workshop. National Park Sierra Lacandon is facing unprecedented deforestation. Defensores de la Naturaleza is making a valiant effort to protect the forests of this officially protected area. Teachers and public health promoters employed by Defensores will be teaching Aves de mi Mundo, a curriculum of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology used by CCFC in our Kids & Birds program. This teachers training was a strategic step in promoting conservation in village schools within the national protected area.

The Sierra Lacandon is located in norther Guatemala (southwestern Peten) along the Usumasinta River which forms the border of the Peten and Chiapas, Mexico. Officially the national park is a protected area but there have been many land invasions and today deforestation is rampant within the boundtries of the park.

September 18 — 21, 2017

September 18 — 21, 2017

Much of the country of Guatemala is on Red-Alert these days as tropical storm Nate passes by along the Atlantic coast of Central America. Many people in Honduras, Guatemala, Belize and Mexico are experiencing heavy rains, mudslides and other weather related set backs.

At CCFC, we are all fine. The buildings are high and dry and we’ve not had any damage. This is a great test of the quality of our new roof. And you will be happy to know that the roof is performing excellently well under the heavy rains. However the river has grown and covers a good part of the low pasture area.

I love the sound of rain. I grew up on Salem, Oregon in the early 1970s. Rain was a part of my childhood soundscape. The steady drizzle of rain was my white-noise, the sound that was almost invisible but strangely comforting to me falling asleep on the upper bunk.

Today, in Guatemala the steady sound of the rain falling outside my office window is not as soothing as it once was. Just a few days ago, on the far side of the mountain a major landslide and several minor landslides destroyed a village, killing six people and damaging many homes and vehicles. On this side of the mountain the rain was hard and steady.

Alta Verapaz is no stranger to rain. However, across Guatemala, rain events are becoming harder and damaged caused by hard rain is becoming more frequent. Today there was another landslide in western Guatemala and news of flooding along the south coast.

Clearly there are several things going on here. It has been abnormally warm in Guatemala for this time of year. Warm air holds more moisture than cool air. So when it does rain there is simply a lot more water up in the sky due to the warmer temperatures. That’s one.

There’s another thing going on that makes landslides more frequent now than before. Forests are temperature fluctuation buffers. A forest moderates temperature spikes. If suddenly the sun comes out and it gets very hot above a cattle pasture or a corn field there is a spike in the ambient temperature. The energy of the sun hits the surface of the field and most of it bounces back doubling the heating effect. If the sun comes out and it gets very hot above a forest, the energy of the sun is captured by the forest and less of it bounces back. Thus the forest prevents a spike in the ambient temperature. Think of it as a buffer. In the 1970s, when forests covered the vast majority of the Verapaz, this amounted to a huge buffer. Old people in the region, especially in the mountain villages, say that when they were children they would never hear thunder. Today thunderstorms are common, even weekly.

Today there is less forested land. Temperatures that are running a bit on the warm-side anyway, now spike. Once gentle rains are now hard rains.

Forested slopes can withstand hard rains without landslides. The trees keep the surface water percolating down into the ground water. As it turns out, cloud forests are the most absorbent of forests. Cloud forests are like great sponges, much more so than pine forests. But when a mountain is deforested, slopes cannot withstand the torrential rains. Less water soaks in. More water flows down as surface water. The soil heavy and saturated with water gives way under its own weight. Once a landslide starts, it grows, gathering mud and rocks and debris. The consequences are sometimes deadly.

In short, in a world of increasingly cataclysmic weather events, forests are our best friends. Forests moderate the climate. Forests catch water and help it soak in. Forests help recharge the ground water. Forest can help prevent landslides. As the haunting lyric of a 1960s Bob Dylan song reminds us, “It’s a hard rain that’s goin’ fall.” So let’s protect our forests.

Water, water everywhere and not a drop to drink:

At the same time, municipal water supplies in this region are having a hard time keeping up with demand. So strangely we have more rain and less water. We have more rain because we have harder rain when it does rain. Coban’s municipal water supply has charted a subtle decrease in water coming into the city’s water supply system, even as demand is on the increase and rains have become increasingly more torrential.

So what’s going on. Why is it that Coban has more rain and less water?

The answer probably lies in forest cover, specially the dwindling forest cover of the mountainside. The cloud forests on the Xucaneb mountain are the recharge zones for the springs that provide Coban with clean, healthy water. Take an extreme example: Haiti.

“It is estimated that 5.4% — 6.9% of Haiti’s precipitation recharges groundwater; this recharge was much higher during the early 1900s when forested lands encompassed 60% of Haiti (Williams, 2011). While deforestation reduces the loss of water from transpiration, it increases surface runoff and soil loss, leading to reduced groundwater infiltration. Presently, forest cover accounts for only 1.5% of Haiti (Singh and Cohen, 2014). For comparison purposes, Döll and Fiedler (2008) estimated the Dominican Republic’s groundwater recharge to be in the range of 8.6% of annual precipitation. The Dominican Republic has forest cover of 40.8% for the period of 2000—2014.”*

So 8.6% of the annual precipitation of the DR recharges its springs and its aquifers. Between 5.4% and 6.9% of Haiti’s annual precipitation recharges its springs and aquifers. So the DR gets to keep more of its water. When water runs off a steep mountain slope it carries with it, soil and soil nutrients. So rain is beginning to make Haiti poorer as it washes away its top soils. But in the DR more of that rain water soaks into mountain slope and comes out gradually in springs. You could say that rain makes the DR richer. Two small countries on one small island. One country with only 1.5% forest cover and the other with nearly 41% forest cover. One country keeps only 5.4% of its rain, while the other country gets to keep 8.6%. If once these two neighboring countries had approximately the same groundwater recharge rate, then Haiti lost

The more forest we lose the more we lose the ability to recharge our springs and aquifers. The less rain we absorb, the more surface water ends up running off with our topsoil.

We moved to San Juan Chamelco in 2001. From time to time we would see the fire truck would park beside the river, sucking up water into its tank, to take into into the town. In those days you would really only see the fire truck hauling water at the height of the dry season, say the end of April. Today, you see not one but two fire trucks hauling water any day of the year. The municipal water supply of San Juan Chamelco is in trouble. Demand is going up and supply is going down. The same is true in Coban, Carcha, Santa Cruz, and San Cristobal.

The problem of deforestation has to be addressed. If not, landslides will continue to be more and more common. Recharge potential of springs will diminish, leaving springs with lower water output.

* James K Adamson and Gérald Jean-Baptiste, “Summary of Groundwater Resources in Haiti” found in Geoscience for the Public Good and Global Development, page 141, edited by Gregory R. Wessel, Jeffrey K. Greenberg, 2016

As CCFC gets ready to receive another group of enthusiastic leaders-in-formation, it is a great moment to look back and see how far we’ve come.

Here is a photo from WALC, fall 2014. Notice the building behind the students. The roof was not yet complete and the walls and windows were not yet finished.

Here is a photo from WALC, fall 2015.

Here is a photo from WALC, fall 2016. Building finished and in full use. We had nearly 100 students sleeping in the building that fall.

Every year WALC has grown and improved.